Africa’s children are paying for COVID-19 with their futures

Smart debt relief is a must

Dakar and Nairobi – While the global spotlight remains firmly fixed on the battle against COVID-19 in wealthy countries, the life and death challenges faced by populations in developing nations, especially children, have steadily worsened over the past 12 months, largely in darkness and with only tokenistic support from global institutions.

COVID-19 has spared no country. But for people living in sub-Saharan Africa, the pandemic magnifies a long list of troubles. Start with economic growth. Before the pandemic struck, the economy was moving so slowly that it would have taken the average person around 45 years to double their income. Then, almost instantly, nearly 15 years of income progress disappeared. Even more troubling, sub-Saharan Africa will be the world’s slowest growing region in 2021: barely 1 per cent on a per capita basis.

Poverty records are being shattered. Using the $1.90/day international definition, an estimated 50 million people have been pushed into extreme poverty in the region in the past year. This is the biggest change ever recorded.

Add on lost learning – that’s around 350 million children who have not gone to school; growing levels of hunger and malnutrition – around half of the population is currently affected by food insecurity; the re-emergence of basic health threats – like cholera, malaria and measles; and rising protection risks – from teenage pregnancies and child marriage to sexual, physical and emotional abuse, and much of the continent is facing a human capital catastrophe.

Better social services build human capital, economic potential and hope for a better tomorrow. Don’t let debt end that hope.

COVID-19 is just one of many drivers. In addition to the economic and viral pains, most countries are also dealing with climate shocks, ranging from droughts and floods to cyclones and locust invasions, as well as intensifying insecurity.

These were among the many dark clouds hanging over the recent Spring Meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank, where finance ministers, central bankers, private sector executives and others debated ways to fix the COVID-19 mess. For citizens of the region, the outcomes were disappointing: global decision makers did not agree that their governments need meaningful assistance to protect people in this moment of extraordinary need.

Even when combining domestic stimulus and all forms of external assistance, the average person in region has benefited from around US$40 in emergency support since the start of the crisis. Compare that to US$2,400 for citizens of G20 countries.

Given the astronomical funding gaps and severe pressures on domestic revenue, it should be easy to forge global consensus for new support to the continent. Think again.

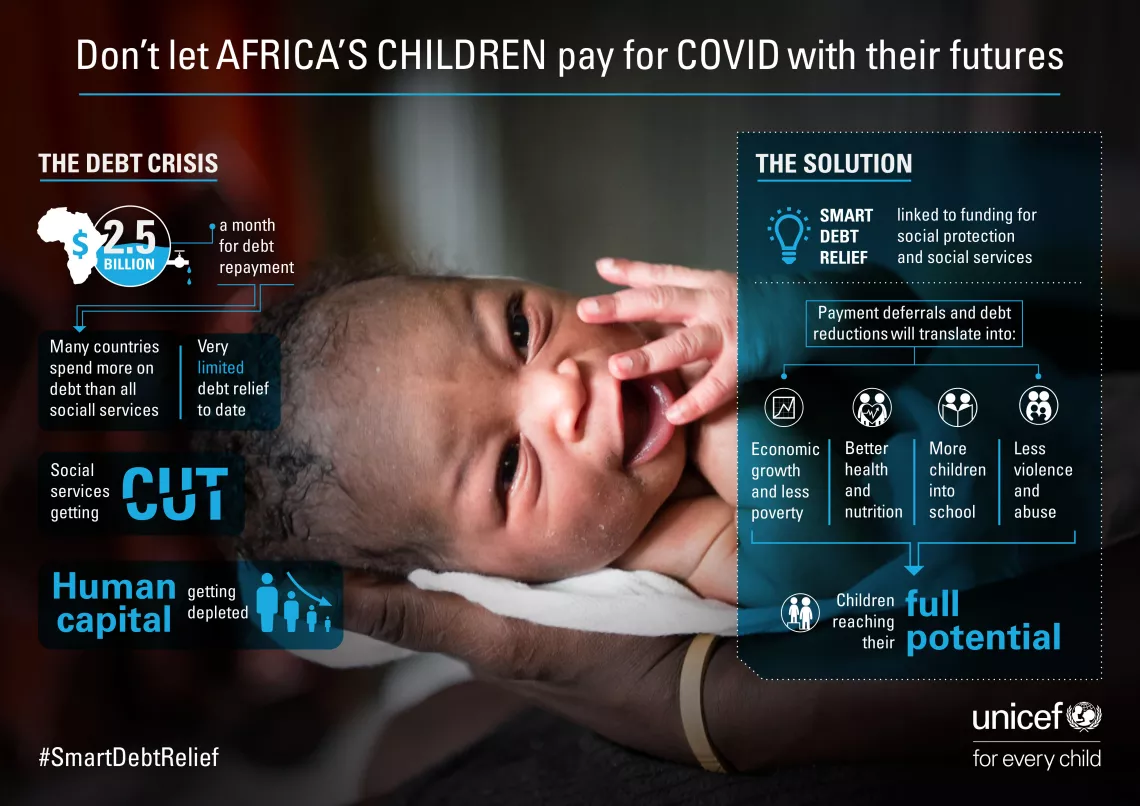

The numbers speak for themselves. Prior to COVID-19, 16 of the poorest governments in sub-Saharan Africa were spending more on servicing debt than on all social sectors combined. The difference was three-fold in places like Chad and The Gambia, and as high as 11-fold in South Sudan. And despite some help through the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), around US$2.5 billion continues to flow to creditors beyond Africa’s borders each month instead of into the futures of children.

We’ve now reached the point where every Shilling, Franc or Rand going to service debt is one less for healthcare, social protection, education and other essential services. UNICEF sounded this alarm bell just ahead of the Spring Meetings in a report entitled A Looming Debt Crisis.

Smart debt relief

Many African governments are spending more on debt payments than on investments in their citizen – more than all spending on education, healthcare and social protection combined. Something has to change. Using debt relief to support greater investment in human capital is part of the answer. We call this Smart Relief.

Unlike the coronavirus, Africa’s debt crisis is not novel. Debt has, in fact, nearly doubled, on average over the past decade. But most of this was for investing in productive capacities and people. The problem is that repayment terms never accounted for a pandemic-induced global recession and an unthinkable collapse in public revenue.

Like most governments, African nations are looking for opportunities to increase spending, whether by reducing interest bills or accessing fresh funding. To put this in perspective, in the last 12 months, the United States has borrowed approximately US$17,000 per citizen to finance stimulus and family support programs, with Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom closer to US$10,000 per head. Sub-Saharan Africa is looking for much less, about US$365 per person in new support to make ends meet over the next five years – or US$73 annually.

To avoid a debt repayment/irreversible-loss-in-human-capital tradeoff requires an international debt restructuring architecture: one that creates the foundation for an inclusive and sustainable socioeconomic recovery for all Africans.

In line with fiscal responses elsewhere, governments in sub-Saharan Africa should be able to put social protection at the center of their crisis response and recovery plans. Cash transfers, in particular, can prevent or minimize nearly every risk that vulnerable households and children are facing right now; they can also generate powerful economic growth.

So, let’s link debt relief to funding for social protection. We call this “smart debt relief” for three reasons. First, it avoids an unacceptable situation whereby debt servicing contributes to a vicious cycle of lending. Second, it releases and channels finance to where investments are most needed: families and children. And third, it catalyzes more than a decade of momentum, as governments across sub-Saharan Africa have adopted policies, launched national cash transfer programs and made them part of their development plans.

Smart debt relief must start with extending the DSSI through 2023 (it currently expires in December) and providing some debt forgiveness to the neediest governments that guarantee new spending on social protection. It also requires that the G20 Common Framework be institutionalized to coordinate the rescheduling of debt held both by official bilateral and private sector creditors, again with greater flexibility for countries that demonstrate social protection commitments. Most importantly, smart debt relief must be complemented by additional support, including grant and highly concessional finance, so that sub-Saharan African countries have a realistic chance of closing funding gaps and protecting human capital.

The next time the world gets together to debate the future, whether it be the United Nations General Assembly (September), the IMF and World Bank Fall Meetings or the G20 Summit (both in October), let’s make sure that the spotlight shines brightly on Africa’s children and practical ways to get them the help they need. Smart debt relief should be viewed as a first step in a much larger support package for the continent, for its children, and its economic and development potential.

Written by Matthew Cummins, Social Policy Regional Adviser for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa, and Paul Quarles van Ufford, Social Policy Regional Adviser for UNICEF West and Central Africa.